Positive Effect of Cell Phones on Families Google Scholar

ane. Introduction

Since the end of the 20th century, the intensification and scope of the utilise of new electronic media by children and young people has been growing systematically. However, this mainly relates to the entertainment and communication functions offered past these types of devices [1]. Today, the mobile telephone has become an indispensable element in the lives of children and adolescents [2]. Specifically, every bit the International Data on Youth and Media reports for 2019 indicated, at that place has been a dizzying increment on the use of mobile phone, especially at younger ages [3,4], which places the start of the interaction with this device from the historic period of seven [v]. This is due to the changes in lifestyles being experienced past young people as a result of the advent of the information guild [6].

Thus, in that location has been an enormous increase in children'southward and adolescents' utilize of mobile phones by in the early stages. This increase is associated with two variants of its employ, the chatty skill that focuses on calls, letters and, mostly, use of social networks [7] and, on the other mitt, the recreational one, which has to do with the viewing of multimedia material and the practise of several mobile games [viii]. Similarly, the arrival of events such equally the YouTuber miracle, which turns immature people into not only receivers but also creators of their own content, has led to an increase in the consumption rates of mobile devices in contempo years [9,x].

Children and adolescents seek to discover, explore and investigate the potential of these devices, this being, in most cases, in an autonomous fashion. This tin can lead them to experience age-inappropriate situations. Lack of maturity and skills to manage inappropriate content have even led some of them to experience psychological, physical discomfort or specific behaviours, such as phubbing or nomophobia [11,12,xiii,14,xv].

At that place is a debate about the permissiveness of mobile phone use in schools. At that place are several experts who advocate the advantages of mobile devices in schools, arguing their novelty, the attraction they produce on students and the wide range of educational offerings with which they provide the teacher, by providing new educational activity/learning strategies [16]. Based on these ideas, multiple studies have incorporated these devices into their educational do, obtaining a successful response from students [17,eighteen,19,20].

On the other manus, amidst those who advocate the disadvantages of mobile telephone use in the educational field, they distinguish several identified risks associated with mobile telephone use in the youth sector. Amidst these, the threat that generates the highest fear is its enormous addictive potential [21,22]. This refers to the notion that digital devices physically and psychologically stimulate the man brain. This is where receiving a "Like" on Facebook or Instagram becomes a priority to be achieved past today's youth [23,24]. Several experts have analysed the potential use of these devices throughout the day in children and adolescents [25], concluding that information technology is necessary to know the attitudes of use of immature people in each context in lodge to promote preventive attitudes that would encourage a responsible utilize of these devices.

Thus, at that place is also a vision in which the popularity of mobile phones is not synonymous with making skilful use of them. In relation to this idea, there is research that shows the relationship betwixt the use of mobile phones on school bounds and lack of concentration, of reflection and criticism, or poor schoolhouse performance by students, which seriously affects their school functioning as a whole [26,27,28,29]. Likewise, the literature too provides the possible relation betwixt the utilise of these devices in the schoolhouse and the increase of cases of school bullying and cyberbullying [30,31,32]. This has led to a ban on the use of mobile phones in schools in several countries. Nonetheless, there are several experts who claim that banning the use of mobile devices in schools is non the solution to eradicate the events of addiction that are being observed in order [33].

Therefore, in that location is a clear need to identify which are the attitudes towards mobile phone employ in each context, in order to provide relevant information that leads to the development and subsequent implementation of measures to solve and forbid this phenomenon.

As a result of this idea, this research aims at understanding attitudes towards mobile phone utilise past children and adolescents, specifically in the Czech republic, in order to provide a full general framework of data on the child–mobile telephone relationship both in their everyday life and in the school setting. This objective can be stratified into the following specific subobjectives:

- -

-

Which activities are the most frequented by young people when interacting with the mobile device.

- -

-

Which activities are carried out by young people during school breaks.

- -

-

Which activities are virtually frequented past young people in the centres where the apply of mobile devices is forbidden.

2. Materials and Methods

ii.1. Research Identification

The research Czech Children in the Cyberworld was carried out by the Center for the Prevention of Virtual Risk Communication at the Faculty of Education of Palacký University in Olomouc, in cooperation with O2 Czech Republic. It is based on the enquiry projects on risk behaviour of kids and adults in the on-line sphere, completed by the very aforementioned squad in 2015–2018 and, in particular, on the following studies: The risks of Internet communication Iv (2014) and Sexting and risk behaviour of Czech Kids in Cyberspace (2017), complementing them with new findings, something unique in the Czech Commonwealth. The analysis of the dataset and the interpretation of the results were carried out in collaboration with the Area inquiry grouping (HUM-672), Department of Education and Schoolhouse Organization of the Academy of Granada (Espana).

The study was funded by O2 Czechia within the framework of the so-chosen contract research. No public or European union funding was obtained.

The written report was conducted co-ordinate to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and ap-proved past the Ethics Committee of Palacky Academy of Olomouc (REF:8012/2020), 2 Dec 2020.

two.2. Procedure

We selected an anonymous online survey as the core research tool. It was distributed to primary/ kickoff years of secondary schools in all regions of the Czechia, where data were collected. The information were collected from one Feb 2019 to ane May 2019. The evaluation and interpretation of the part results was completed in the following weeks. Prior say-so was sought from each of the students so that they could participate in the research. The Cronbatch alpha coefficient was valid (α = 0.879). The survey was distributed through the Google Forms software.

The questions asked in the survey aimed at exploring which habits they had in their daily school life and in their free fourth dimension, as well as during class periods. The questions mainly focused on how they used their cell phones and how oftentimes they did then (chatting on their jail cell phones, using social networks, etc.). Equally for data analysis, the relevant statistics were processed and performed using the Statistica software.

ii.3. Participants

A total of 27,177 respondents aged 7–17 from all Czech regions participated in the inquiry and boys constituted 49.83% of the sample. The average historic period of all respondents was thirteen.04 years (median xiii, modus 12, variance iv.34). The sample configuration was carried out through simple random sampling, in which unlike schools were randomly selected from the different Czech regions to participate in the completion of the questionnaire. Afterwards, those pupils whose parents gave their consent to participate formed the research sample. Responses came mainly from schools in Moravskoslezský, Olomoucký and Středočeský (Czechia), with a response rate of 75.3% of their total schools.

iii. Results

3.1. A. Children and Mobile Phones

In our research, we focused on active usage of mobile phones by children. We wanted to know whether a child had a mobile telephone with Cyberspace access without the need of Wi-Fi connectedness (due east.g., through 3G, 4G, LTE, etc.). Over half of the children (59.1%) confirmed that they had permanent Internet access on their mobile phone and, therefore, did not have to rely on Wi-Fi (Table one).

The almost frequent activity reported past children was making/receiving phone calls (72%), followed past typing and sending messages on on-line services (Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, etc.) (66%). The post-obit identify was taken by watching videos on YouTube and typing SMS letters.

3.ane.1. Mobile Phones in Schools

A question that echoes strongly in the Czech Republic, also as in other European countries, is how to regulate the children's use of mobile phones in schools—whether to ban mobile phones during lessons and breaks or to limit the ban only to lessons and not breaks (see the stance of the Czech Schoolhouse Inspectorate). Therefore, we asked children most their experience with mobile phone restrictions and how this event was dealt with in the school they attended (Table 2).

The majority of children (53.3%, fourteen,486 children) were permitted to use mobile phones during recess at school and this was not permitted during classes. However, at the teacher'south teaching, they were also allowed to use their mobile phones during lessons—the mobile telephone becomes a learning aid/tool. However, a meaning number of children (41.20%, i.e., eleven,198 children) could not use the mobile phone at school at all, not fifty-fifty during recess.

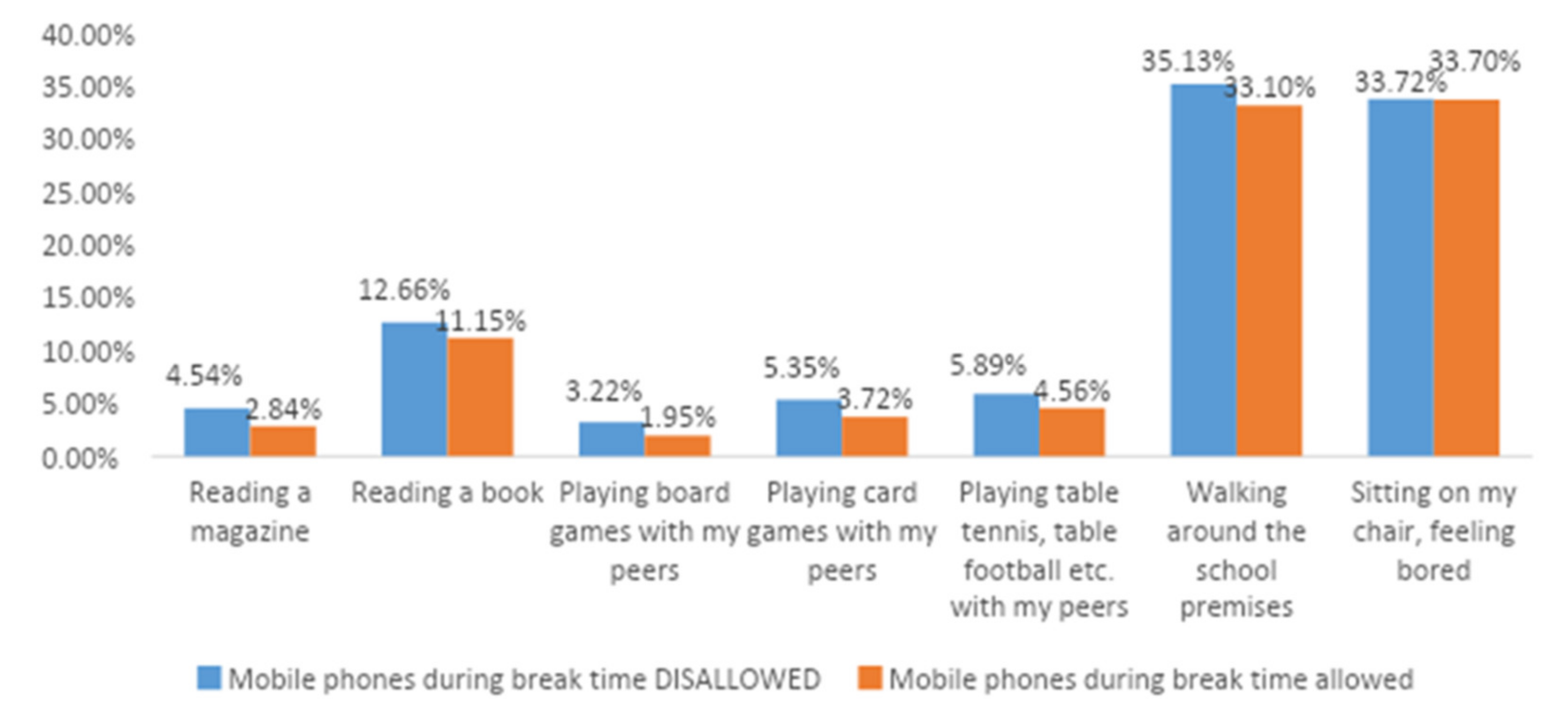

In relation to the use of mobile phones in school, we wanted to know the mode children spent their intermission time, so nosotros asked what pupils did during break time. Looking at the overall summary of well-nigh frequent interruption time activities, we constitute out that communication with peers dominated (85.24%). However, we do non know how the bodily communication goes, i.e., what pupils actually talk virtually. However, a clear difference in the way of spending break fourth dimension was visible betwixt schools with and without mobile phone restrictions (Tabular array iii and Table 4).

Methodology comment: We divided the sample into ii groups, to be compared to each other. Both groups included approximately the same number of respondents and when calculating pct differences, we worked with relative frequencies. Respondents were allowed to give multiple answers at the same fourth dimension, i.e., the child was, for instance, immune to use a mobile phone when walking on the school bounds. The following results evidence an overview of the most frequent break time activities.

In the enquiry, nosotros likewise differentiated between activities of children in the primary tier and get-go years of the secondary tier. The results are presented in the following charts (Table 5 and Table 6). The application of the chi-squared confirmed that the statistical differences between the responses obtained in the two types of centres are significant (p value < 0.001).

The departure is obvious—where mobile phones during break fourth dimension were allowed, activities related to mobile phones clearly dominated (Figure 1). The acme activity was playing games, preferred past over 40% children in schools where mobile phones were immune during suspension fourth dimension. The 2d place was taken by the use of social networks (almost 39%). In improver, a significant number of children passively watched their peer's games or videos—22% more than in schools where mobile phones were immune, compared to schools that prohibited mobile phones.

Interestingly, approximately 1 tertiary (33%) of children felt bored during break times (33%), regardless of mobile phones during break fourth dimension existence immune or non. As for moving effectually the school premises, this was not influenced by mobile phones being allowed or restricted. In schools with a total mobile phone ban, approximately 6% more than children walked around, compared to schools with mobile phones allowed.

Obviously, a mobile telephone ban likewise affects the frequency of activities that are not direct related to mobile phones—reading, sport, non-virtual amusement. In schools where mobile phones were banned during break time, the number of children reading magazines during break time was almost sixty% higher than in schools where mobile phones were immune. An increase was also obvious in reading books (+13.54% on schools with the ban), playing lath games (+65%), playing card games (+43%) and sport activities (+29%). Banning mobile phones during suspension time has, therefore, a existent bear on on the development of such activities.

It has to exist said that, although mobile phones during break time might be banned past a school, some children practice not comply. For instance, v% children played games on their mobile phones although gaming was not allowed, five% also used social networks regardless of the ban in identify, 4% chatted with other people although information technology was not allowed, etc. However, a significant decrease was present in all observed activities, in comparison with schools where mobile phones were allowed.

3.1.2. Taking Photos/Videos by Peers without Their Consent

In relation to mobile phone restrictions in schoolhouse, it is often pointed out that a mobile phone in schoolhouse might be misused, for case to picturing peers without their consent. Therefore, we wanted to know how many children had experienced, in school, that someone made photos/videos of them without consent—during break time, lesson, or a school event.

A total of 35.71% children (9706 children in our sample) confirmed that they had been photographed past a peer without consent and 22.5% children (6115 children in our sample) confirmed that they had been videoed by a peer without consent. It is clearly not a marginal event.

4. Word

Nowadays, the use of mobile phones amidst young people in the Czech Republic has increased considerably. This has given rise to the concern of unlike teaching professionals to study the use of mobile phones inside and outside the schoolhouse environment and the risks that exist as a result of this phenomenon.

Based on this idea, the present research aims to measure out the behaviour of Czech children and adolescents with regard to the use of mobile phones. Thus, the results presented show a articulate mental attitude of boredom in which young people do non notice entertainment unless they take the technological tool at their disposal.

More than one-half of the children confirmed that they had permanent access to the Internet on their mobile phone, without having to rely on Wi-Fi (e.k., at school or in a library). They used their mobile phones most frequently to make/receive calls, write/send letters, watch YouTube videos, accept photos, play games or listen to music. In this sense, a line is established that coincides with studies such as [nine] or [10] with regard to how these activities are condign increasingly important in the daily chores of children and young people, especially the use of social networks or the massive employ of platforms such as YouTube [21,22].

Furthermore, there are also concerns virtually the possible risks of techno-addiction that this may cause in young Czechs [21,22]. Similarly, the large percentages expressed in the results of this study could have a possible impact on the lack of concentration and dispersion, which are straight related to schoolhouse operation [26]. In this sense, the lines established coincide with other previous studies [28].

In plough, we focused on break time and explored the touch of the prohibition/permission of mobile phones on their activities. Virtually children were allowed to use mobile phones during recess at schoolhouse and were not allowed to use them during lessons. Where mobile phones were allowed, the dominant activity was playing with them, using social media and being bored in the chair.

Interestingly, we constitute roughly the aforementioned number of bored children in schools where mobile phones were banned during recess. In schools where mobile phones were banned during recess, the dominant action was walking effectually the school grounds, sitting on a chair, feeling bored and reading books, followed by sports activities and card games. The application of the chi-squared examination confirmed the existence of significant differences betwixt the two groups. This undoubtedly creates a argue around the current motivations surrounding young people's entertainment. We find ourselves in a context in which the Internet and the use of mobile devices occupy a large percent of immature people'due south overall entertainment throughout the day. Given this evidence, it is necessary for parents and educators to establish a debate about the motivations of immature people and how to encourage good for you leisure and free time habits, also as reducing the use of mobile devices [10].

In this respect, when comparing the two samples, in schools where mobile phones were banned during recess, the number of children reading magazines during recess was most 60% higher than in schools where mobile phones were allowed. An increase in volume reading, board games, bill of fare games and sports activities was likewise observed. Therefore, information technology could be indicated, in line with previous studies, that mobile phone use is useful and can have a functional apply within the school, as stated in recent research [16]. Yet, it is necessary to regulate their employ within the schoolhouse, with the aim of promoting leisure, socialisation, sport or reading activities, which undoubtedly promote greater benefits for children and adolescents.

Equally a result of all these ideas, the aim is to share some ideas with educators and professionals in this field, providing a series of myths related to the utilise of mobile phones at schoolhouse, every bit well equally expressing the need to promote their proper apply and regulate their use.

A. Myths related to mobile phones in school

There is a wide range of myths on mobile phones in the school environment, ofttimes shared by non-professionals, such as parents, who often do not empathize how mobile phone restrictions work and to whom the bans really apply. We volition focus on the most widespread ones.

Myth no. 1—A mobile phone ban in school ways that phones are also banned during lessons.

One of the virtually frequent arguments in discussing mobile phones in school is based on the premise that a telephone is a tool that can be effectively used in education (every bit a method of delivery, source of data, etc.) and a mobile phone ban will deprive usa of such benefits. This is obviously misunderstood—mobile phone restrictions in school employ to pupils' activities outside the blessing and education from their teacher! It does not apply to situations when a teacher asks pupils to have out their phones and apply them actively for a learning chore. At this point, a mobile phone becomes a learning tool and we should non worry about children using it in lessons. A mobile phone ban, in fact, does not restrict the teacher's work, or the activities organised by the teacher. Smartphones can be therefore freely used for any meaningful activeness organised past the teacher.

Myth no. 2—The use of the phone as a condom measure for emergency situations.

Myths presented mainly by parents include the belief that a phone tin can ensure their child's safety in an emergency. Therefore, their child should always accept a mobile telephone fix to phone call for help while in school. Beginning, it has to be said that safety and protection of children during school time is the responsibility of their school. It is the school that provides safe (and this must be ensured past the school management or governing body). If a pupil gets injured in school, information technology must exist reported to a instructor/deputy/principal instead of phoning home. The incident is dealt with by the school, that must inform parents. Teachers could even get to prison if a child is harmed equally a result of a teacher's negligence! For emergency situations, schools have crisis management policies in place, describing what to exercise with every specific trouble (incident). Moreover, using a mobile phone in emergency without the teacher's noesis is non desirable—information technology tin raise panic among the parents contacted by the child, although aught serious really happened and it is only the child wanting to share their emotions with their parents. Similarly, a child can initiate an intervention by rescue services although the incident could take been sorted easily on the spot.

Myth no. three—A mobile telephone in school is necessary for parents keeping their child permanently under control.

This myth is closely related to the previous 1. It has to exist noted, again, that parents should NOT control their children during school time. This is the responsibleness (and the related liability for any issues) of the schoolhouse. If parents need to send an urgent bulletin to their child, they can e'er contact the schoolhouse part or the specific instructor. The contrasts in this discussion are interesting—parents want freedom for their children, only, at the same time, they want to control them strictly, even while the children are in someone else's care.

Myth no. iv—During intermission times, children should enjoy the freedom they do not have during lessons. Past restricting mobile phones, we suppress their liberty.

This argument is often used by those who do not realise that even intermission times between lessons take a purpose. These are not the child'due south "free fourth dimension" but they found a function of the educational process. Break times are in place particularly for a short rest (both listen and body), preparation for the upcoming lesson, time for physiological needs and interpersonal communication necessary for the kid's participation in a social group (simply "chit-conversation and gossip"). A school is actually one of few places (except afterschool clubs and classes) where a child can socialise through directly contact, which cannot be replaced by online chatting and sharing. It helps to develop non-exact communication skills (facial expression, gestures), conflict resolution and coping skills, mutual respect, simply also concrete characteristics (smell, physical power), etc. These cannot be simulated through technology. Children go their free time later the last lesson or dejeuner every solar day. From that moment, they tin can apply their mobile phones freely, within any limits set by parents. They can contact their parents while staying in an afterschool club (although regulation is desirable hither as well).

Myth no. v—Banning mobile phones in school will result in the prohibition effect—phones will exist used secretly.

This has not been confirmed by schools that have been keeping strict limits for some time. A wisely managed schoolhouse introduces a mobile telephone ban along with new opportunities. To introduce a mobile phone ban on the bounds, the schoolhouse must have a sufficient range of relax and sport zones available (a place for brawl games, table football game, table tennis, board games, construction toys, chairs, books, chill-out zones, art and musical equipment, an open-air space for a walk, etc.).

The above-mentioned prohibition upshot only accompanies the first stage of "going non-mobile" (this phase, according to reports, lasts for almost a month), like to an addict'south withdrawal symptoms—pupils must of a sudden entertain themselves, put some effort in establishing communication with others, make concessions, resolve conflicts and practice other social skills. Moreover, this tin exist difficult for someone who interacts mostly with electronics. The prohibition effect emerges almost exclusively in schools that do not accept a sufficient offer of inspiring activities in identify. Therefore, it is considered suboptimal to promote the prohibition of cell phones in Czech schools. In the same vein, information technology follows the aforementioned line of [33], in which the prohibition of mobile phones in the classroom is considered to exist ineffective.

B. Regulating the use of mobile phones in schoolhouse

Limiting the utilise of mobile phones during break times does not harm children at all—on the contrary, it has a significantly positive effect on them. Information technology offers something that cannot be provided by family and applied science—in particular, a chance to socialise direct (and the related set of skills to resolve conflicts, institute and maintain existent friendship, manage their emotions, command their own behaviour, try out new opportunities, interruption rules and take responsibility for it, succeed in arguments, etc.). However, it is ever necessary for the schoolhouse to provide space for meaningful costless-fourth dimension activities—chillout zones, sport zones, etc.

Regulating the utilize of mobile phones is desirable and meaningful, particularly in preschools and primary schools (upward to 12 years of age). Afterward, the restrictions can be gradually eased out.

C. Positive means of using phones for learning

Smartphones, tablets and other touchscreen mobile devices present a wide range of technologies that tin be easily exploited in both schoolhouse lessons and for homework. In addition, they are role of and then-called BYOD (bring your own device) concept, where children actively utilize devices brought from habitation. Smartphones can be used for learning in several ways. The simplest method is presenting text, audio/video footages, animations, visualisations, schoolhouse projects, digital learning programmes, etc., on the screens. Smartphones and tablets can be linked to interactive whiteboards and the learning content tin can exist easily presented to the entire grade.

Another option is to use touchscreen devices for electronic textbooks (ebooks). These allow, apart from merely presenting the learning topics, interaction with active elements (hypertext links, interactive tasks, etc.). In fact, many publishers now provide their classic paper textbooks forth with an electronic version, extended by features, such as automatic evaluation of exercises and tasks or multimedia content that cannot be presented in a paper textbook. With modern electronic textbooks, teachers can simulate a range of processes and phenomena that are no longer demonstrated in schools today, such equally autopsy of an brute, dangerous chemical reactions, insight into complex mechanisms, etc.

A smartphone or tablet can exist also used for collaborative learning. There is a wide range of applications bachelor, allowing users to share a whiteboard, create shared mental or terminology maps, or shared message boards, communicate with each other, vote in polls, test and internalise their cognition through many test programmes, etc.

A smartphone or tablet can be naturally used as a gateway to the Cyberspace and online services. Pupils tin can utilise it to search for and verify information, download content, lookout man videos, programme routes, communicate, vote, test their noesis, etc. A smartphone can also be used as an augmented reality or mixed reality tool. Augmented reality allows inserting virtual elements (text, videos, 3D objects) into "real" reality through a mobile touchscreen device.

Cheers to their mobility and battery life, mobile phones and tablets are great for enquiry/discovery forms of learning. Watching and time-lapsing wild fauna, determining fauna and flora species, tracking location (longitude/latitude, acme), discovering the laws of nature, etc., can be all done with a smartphone. In this sense, this coincides with studies carried out in other countries that support the integration of these technological resources in the classroom, equally well as their standardization within the school [17,eighteen].

v. Conclusions

Czech youth find themselves in a situation where a large part of their leisure time at school is spent in contact with mobile phones. In cases where the use of these devices is prohibited on schoolhouse grounds, information technology was reported that many of them were bored and did not know what to exercise.

From this work, we identified this pattern of behaviour among young Czechs, which is undoubtedly a concern for their personal and educational future. Nosotros detect ourselves in a context in which technologies boss most of young people's time, leaving aside good for you lifestyle habits, such as sports. Equally a outcome, the rates of addiction to mobile phones and the Internet may increase, which are nowadays and time to come threats in young people's society. The aim of this piece of work is to plant the facts around the question of the behaviour of Czech children and adolescents.

Furthermore, the primary education stage should serve as a preventive measure to promote responsible habits in children with regard to possible attitudes in adolescence [34] with respect to the use of mobile phones and the threats that exist on the Cyberspace.

Therefore, nosotros advocate the need to promote educational policies in educational centres, which, through a coordinated practise with families, should promote the implementation of activities of various kinds to stimulate children to reduce the use of mobile phones. It is as well considered that prohibiting their use in educational centres may not be the most effective option for achieving favourable results. Therefore, the integration of mobile phones in the classroom in a responsible way by educational centres could exist a way to normalize their employ in the classroom and prevent students from feeling the desire to use these devices in secret.

One of the limitations of this study is that it was not possible to detect out more independent variables in the study sample, which would take provided some additional statistical input, too as the relationships between the dependent and contained variables. Likewise, as a hereafter line of research, it would be relevant to keep studying mobile phone use behaviour in other countries and to establish comparative studies between territories. Likewise, it would be interesting to focus on topics such equally Cyberspace or mobile phone habit in order to provide more empirical evidence in this field of noesis.

In conclusion, while technology has brought many benefits to society, its use in the context of youth needs to exist regulated. Encouraging social and sporting practices past schools, in collaboration with families, will promote a healthier and less disease-prone environs. Moreover, encouraging responsible use of mobile phones volition assistance this social group to take advantage of all the benefits offered by the Internet and its devices and to altitude themselves from the threats that as well reside in them.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Grand. and R.S.; methodology, 1000.G.-Grand.; software, One thousand.Yard.; formal analysis, R.S.; investigation, Thousand.M.; resources, F.-D.F.-M.; information curation, One thousand.One thousand.; writing—original draft preparation, K.K. and G.Yard.-Yard.; writing—review and editing, K.K., G.Thou.-G. and Chiliad.M.; visualization, K.K. and F.-D.F.-One thousand.; supervision, F.-D.F.-M. All authors accept read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ideals Committee of Palacky University of Olomouc (REF:8012/2020), 2 December 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would similar to thank the Centre for the Prevention of Virtual Take a chance Communication at the Faculty of Education of Palacký University in Olomouc, in cooperation with O2 Czechia and the AREA research grouping (HUM-672) from the University of Granada.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no disharmonize of interest.

References

- Tomczyk, Ł.; Kopecký, K. Children and youth safety on the Cyberspace: Experiences from Czech Republic and Poland. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 822–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J.; Sánchez, J.; Trujillo, J. Utilización de Net y dependencia a teléfonos móviles en adolescentes. Rev. Latinoam. De Cienc. Soc. Niñez Y Juv. 2016, xiv, 1357–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besolí, G.; Palomas, N.; Chamarro, A. Uso del móvil en padres, niños y adolescentes: Creencias acerca de sus riesgos y beneficios. Aloma Rev. Psicol. Ciències L'educació I L'esport 2018, 36, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringué, X.; Sábada, C. Niños y Adolescentes ante las Pantallas. In La Generación Interactiva en Madrid; Colección Generaciones Interactivas-Fundación Telefónica; Foro Generaciones Interactivas: Madrid, Kingdom of spain, 2011; Bachelor online: http://dadun.unav.edu/bitstream/10171/20593/1/GGIIMadrid-final.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Lange, R.; Osiecki, J. Nastolatki Wobec Internetu/Teens and Cyberspace; Pedagogium: Warszawa, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cornish, Fifty. 'Mum, tin I play on the net?' Parents' agreement, perception and responses to online advertising designed for children. Int. J. Advert. 2014, 33, 437–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dans, I. Posibilidades Educativas de las Redes Sociales. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de la Coruña, A Coruña, Spain, April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ruvalcaba, Grand.M.; Arámbula, R.E.; Castillo, S.G. Impacto del uso de la tecnología móvil en el comportamiento de los niños en las relaciones interpersonales. Educateconciencia 2015, five, 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kopecký, K.; Hinojo-Lucena, F.J.; Szotkowski, R.; Gómez-García, 1000. Behaviour of young Czechs on the digital network with a special focus on YouTube. An analytical study. Kid. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar, I.; Trujillo, J.Thou.; Romero, J.Yard.; Campos, Thousand.Northward. Generación Niños YouTubers: Análisis de los canales YouTube de los nuevos fenómenos infantiles. Píxel Bit Rev. Medios Educ. 2019, 56, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-García, A.M.; Moreno-Guerrero, A.J.; López Belmonte, J. Nomophobia: An Individual's Growing Fear of Being without a Smartphone—A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, T.; Vocal, 50.; Ning, South.; Wang, H.; Zhang, G.; Wu, Z. Relationship between the incidence of de Quervain'south disease among teenagers and mobile gaming. Int. Orthop. 2019, 43, 2587–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios-Borjas, D.A.; Bejar-Ramos, Five.A.; Cauchos-Mora, 5.Southward. Uso excesivo de Smartphones/teléfonos celulares: Phubbing y Nomofobia. Rev. Chil. Neuro Psiquiatr. 2017, 55, 205–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, H.; Nishida, T.; Tsuji, A.; Sakakibara, H. Association between excessive utilize of mobile phone and insomnia and depression amongst Japanese adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, S. The reciprocal longitudinal relationships between mobile telephone addiction and depressive symptoms among Korean adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 58, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, H.; Burke, D. The apply of mobile learning in higher education: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. 2018, 123, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, S.; Gutiérrez-Colón, M.; Frumuselu, A.D. Feedback and Mobile Instant Messaging: Using WhatsApp as a Feedback Tool in EFL. Int. J. Instr. 2020, thirteen, 797–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetinkaya, 50. The impact of WhatsApp use on success in educational activity process. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2017, xviii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traxler, J.M. Learning with mobiles in developing countries: Technology, linguistic communication, and literacy. Int. J. Mob. Composite Learn. (IJMBL) 2017, 9, i–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, K.; Hampshire, Chiliad.; Milner, J.; Munthali, A.; Robson, East.; De Lannoy, A.; Bango, A.; Gunguluza, N.; Mashiri, Yard.; Tanle, A.; et al. Mobile Phones and didactics in Sub-Saharan Africa: From youth practise to public policy. J. Int. Dev. 2016, 28, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.Q.; Zhou, Z.1000.; Yang, X.J.; Kong, F.C.; Niu, G.F.; Fan, C.Y. Mobile phone addiction and sleep quality among Chinese adolescents: A moderated arbitration model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Miralles, R.; Ortega-González, R.; López-Morón, M.R.; Batalla-Martínez, C.; Manresa, J.1000.; Montellà-Jordana, N.; Chamarro, A.; Carbonell, Ten.; Torán-Monserrat, P. The problematic utilise of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in adolescents by the cross exclusive JOITIC study. BMC Pediatr. 2016, sixteen, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Guerrero, A.J.; Gómez-García, Grand.; López-Belmonte, J.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, C. Cyberspace Addiction in the Spider web of Science Database: A Review of the Literature with Scientific Mapping. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Wellness 2020, 17, 2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.M.R.; Soto, N.C.; Gómez-García, Thou. Follow me y matriarch like: Hábitos de uso de Instagram de los futuros maestros. Rev. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2019, 94, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, Á.D.B.; Fernández, I.R. Hábitos de uso del WhatsApp por parte de los adolescentes. Revista INFAD de Psicología. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 2, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felisoni, D.D.; Godoi, A.S. Cell phone usage and academic performance: An experiment. Comput. Educ. 2018, 117, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, H. El uso de teléfonos móviles en el sistema educativo público de El Salvador: Recurso didáctico o distractor pedagógico? Real. Reflexión 2016, 40, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, L.D.; Carrier, L.Yard.; Cheever, N.A. Facebook and texting fabricated me practise it: Media-induced job-switching while studying. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 948–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, East.; Zivcakova, L.; Gentile, P.; Archer, K.; De Pasquale, D.; Nosko, A. Examining the affect of off-job multi-tasking with applied science on real-fourth dimension classroom learning. Comput. Educ. 2012, 58, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopecký, Grand.; Szotkowski, R. Specifics of Cyberbullying of Teachers in Czech Schools-A National Research. Inform. Educ. 2017, sixteen, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimtsiou, Z.; Haidich, A.B.; Drontsos, A.; Dantsi, F.; Sekeri, Z.; Drosos, E.; Trikilis, N.; Dardavesis, T.; Nanos, P.; Arvanitidou, M. Pathological Internet use, cyberbullying and mobile phone use in adolescence: A school-based study in Greece. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Wellness 2017, 30, 20160115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y'all, S.; Lim, S.A. Longitudinal predictors of cyberbullying perpetration: Bear witness from Korean middle school students. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 89, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn, N.; Aagaard, J. Banning mobile phones from classrooms—An opportunity to advance understandings of applied science addiction, distraction and cyberbullying. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, G.; Kapus, G.; Hesszenberger, D.; Pohl, 1000.; Kósa, One thousand.; Osculation, J.; Pusch, Thousand.; Fejes, É.; Tibold, A.; Feher, G. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Internet Habit among Hungarian Loftier Schoolhouse Teachers. Life 2021, 11, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Effigy 1. Activities carried out during break times depending on the availability of the mobile phone.

Effigy 1. Activities carried out during break times depending on the availability of the mobile telephone.

Tabular array 1. Virtually frequent activities on a mobile telephone.

Table i. Almost frequent activities on a mobile phone.

| Activeness | Full Frequency (n) | Relative Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Making/receiving phone calls | 19.701 | 72.49 |

| Typing and sending messages on on-line services (Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, etc.) | 18.044 | 66.39 |

| Watching videos on YouTube | 17.778 | 65.42 |

| Typing and sending SMS/MMS messages | 14.735 | 54.22 |

| Taking photos | xiv.039 | 51.66 |

| Playing games | 13.457 | 49.52 |

| Listening to music or spoken audio (e.grand., on Spotify, Apple Music, etc.) | 12.801 | 47.ten |

| Searching for information (e.1000., on Google) | 10.400 | 38.27 |

| Watching favourite YouTubers | 9091 | 33.45 |

| Browsing social networks (passive, reading posts) | 8811 | 32.42 |

| Rating content on social networks (liking, rating past emoticons—such as Hearts on TikTok or Instagram). | 8608 | 31.67 |

| Sharing photos and videos on social networks | 7005 | 25.78 |

| Watching videos on TikTok | 5319 | 19.57 |

| Making videos | 4702 | 17.30 |

| Using a mobile telephone for educational purposes (educational apps/videos/content) | 4580 | 16.85 |

| Reading texts on a mobile phone (east.g., text documents, books, PDF files, etc.) | 3969 | fourteen.60 |

| Managing a social network account (managing own wall, managing photo albums and video albums, creating campaigns) | 3900 | 14.35 |

| Watching videos on Twitch | 3588 | 13.20 |

| Streaming videos (e.thousand., through Twitch or Facebook) | 1818 | six.69 |

Table 2. Using mobile phones in school (from the children's perspective).

Table 2. Using mobile phones in school (from the children'south perspective).

| Breaks | Lessons | Relative Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Allowed | Prohibited | 53.30% |

| Prohibited | Prohibited | 41.20% |

| Immune | Allowed | 2.48% |

| Prohibited | Immune | 1.09% |

| Not stated | Not stated | ane.92% |

Tabular array 3. The most frequent pause time activities—schools where mobile phones are allowed during break fourth dimension.

Table 3. The virtually frequent break time activities—schools where mobile phones are immune during break time.

| Activities | Total Frequency (n) | Relative Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Playing games on my mobile phone | 6216 | 41.00 |

| Browsing social networks on my mobile phone | 5898 | 38.90 |

| Sitting on my chair, feeling bored | 5110 | 33.70 |

| Walking effectually the school premises | 5018 | 33.10 |

| Writing to someone on my mobile phone | 4246 | 28.00 |

| Listening to music on my mobile phone | 4190 | 27.63 |

| Watching my peers playing games/watching videos, etc., on their mobile phones | 3364 | 22.19 |

| Browsing websites on my mobile phone | 2422 | 15.97 |

| Watching YouTube videos on my mobile telephone | 2014 | xiii.28 |

| Reading a volume | 1690 | 11.15 |

| Watching TikTok videos on my mobile phone | 1270 | 8.38 |

| Playing table tennis, tabular array football game, etc., with my peers | 691 | 4.56 |

| Making videos on my mobile telephone | 635 | iv.19 |

| Playing carte games with my peers | 564 | 3.72 |

| Reading a magazine | 431 | 2.84 |

| Playing board games with my peers | 295 | 1.95 |

Table 4. The most frequent intermission time activities—schools where mobile phones are not allowed during suspension time.

Table 4. The most frequent break time activities—schools where mobile phones are non allowed during suspension fourth dimension.

| Activities | Total Frequency (due north) | Relative Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Walking around the school bounds | 4329 | 38.66 |

| Sitting on my chair, feeling bored | 3892 | 34.75 |

| Reading a volume | 1667 | xiv.89 |

| Playing table tennis, table football game etc. with my peers | 857 | vii.65 |

| Playing card games with my peers | 835 | 7.46 |

| Reading a mag | 748 | 6.68 |

| Watching my peers playing games/watching videos, etc., on their mobile phones | 627 | 5.60 |

| Playing games on my mobile phone | 611 | 5.46 |

| Browsing social networks on my mobile phone | 595 | v.31 |

| Playing board games with my peers | 536 | 4.79 |

| Writing to someone on my mobile phone | 488 | iv.36 |

| Listening to music on my mobile phone | 451 | 4.03 |

| Browsing websites on my mobile phone | 246 | 2.twenty |

| Watching YouTube videos on my mobile phone | 196 | 1.75 |

| Watching TikTok videos on my mobile phone | 162 | one.45 |

| Making videos on my mobile phone | 130 | 1.16 |

Table v. What practise master tier (7–xi-year-old) children practice during intermission times.

Table 5. What exercise master tier (7–11-year-former) children exercise during pause times.

| Mobile Phones during Pause Fourth dimension Immune | Mobile Phones during Break Time DISALLOWED | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity | Total Frequency (n) | Relative Frequency (%) | Total Frequency (northward) | Relative Frequency (%) | χ2 | p Value |

| Chatting with other pupils | 1959 | 80.55 | 4146 | 87.88 | 167.94 | *** |

| Playing games on my mobile phone | 930 | 38.24 | 92 | i.95 | 146.37 | *** |

| Walking around the school premises | 758 | 31.17 | 1557 | 33.00 | 141.94 | *** |

| Watching my peers playing games/watching videos, etc., on their mobile phones | 686 | 28.21 | 164 | 3.48 | 124.56 | *** |

| Sitting on my chair, feeling bored | 670 | 27.55 | 1330 | 28.19 | 120.97 | *** |

| Listening to music on my mobile phone | 364 | 14.97 | 56 | 1.19 | 76.64 | *** |

| Browsing social networks on my mobile phone | 337 | 13.86 | 36 | 0.76 | lxx.84 | *** |

| Reading a book | 300 | 12.34 | 879 | 18.63 | 67.76 | *** |

| Watching TikTok videos on my mobile telephone | 279 | eleven.47 | threescore | i.27 | 55.94 | *** |

| Watching YouTube videos on my mobile phone | 217 | 8.92 | 46 | 0.97 | 41.64 | *** |

| Writing to someone on my mobile phone | 214 | 8.80 | xxx | 0.64 | 46.64 | *** |

| Playing table lawn tennis, tabular array football, etc., with my peers | 152 | half dozen.25 | 378 | 8.01 | 37.94 | *** |

| Reading a magazine | 134 | 5.51 | 418 | 8.86 | 23.64 | *** |

| Browsing websites on my mobile phone | 117 | 4.81 | 25 | 0.53 | xix.97 | *** |

| Playing card games with my peers | 111 | iv.56 | 453 | 9.60 | 17.xvi | *** |

| Playing board games with my peers | 102 | four.19 | 365 | 7.74 | fifteen.64 | *** |

| Making videos on my mobile phone | 92 | iii.78 | 22 | 0.47 | ix.67 | *** |

| Watching YouTubers on my mobile phone | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | |

| Not stated | 2432 | 4718 | ||||

Table vi. What do offset years of the secondary tier (12–15-year-quondam) children do during break times.

Table half dozen. What do starting time years of the secondary tier (12–15-year-old) children do during interruption times.

| Mobile Phones during Interruption Fourth dimension ALLOWED | Mobile Phones during Break Time DISALLOWED | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity | Total Frequency (northward) | Relative Frequency (%) | Total Frequency (n) | Relative Frequency (%) | χ2 | p Value |

| Chatting with other pupils | 7864 | 85.44 | 5785 | 88.15 | 345.27 | *** |

| Playing games on my mobile phone | 3958 | 43.00 | 536 | viii.17 | 278.69 | *** |

| Browsing social networks on my mobile phone | 3430 | 37.27 | 553 | 8.43 | 245.64 | *** |

| Sitting on my chair, feeling bored | 3105 | 33.74 | 2546 | 38.79 | 237.95 | *** |

| Walking around the school premises | 3247 | 35.28 | 2816 | 42.91 | 244.81 | *** |

| Writing to someone on my mobile telephone | 2316 | 25.16 | 446 | 6.lxxx | 246.97 | *** |

| Listening to music on my mobile telephone | 2573 | 27.96 | 408 | 6.22 | 256.94 | *** |

| Watching my peers playing games/watching videos, etc., on their mobile phones | 2194 | 23.84 | 492 | 7.fifty | 234.64 | *** |

| Browsing websites on my mobile telephone | 1272 | 13.82 | 224 | 3.41 | 202.64 | *** |

| Watching YouTube videos on my mobile phone | 1188 | 12.91 | 155 | 2.36 | 197.82 | *** |

| Reading a book | 960 | 10.43 | 805 | 12.27 | 185.64 | *** |

| Watching TikTok videos on my mobile phone | 820 | 8.91 | 120 | 1.83 | 164.21 | *** |

| Playing table lawn tennis, table football, etc., with my peers | 442 | 4.80 | 495 | 7.54 | 101.64 | *** |

| Making videos on my mobile phone | 418 | 4.54 | 106 | 1.62 | 97.64 | *** |

| Playing menu games with my peers | 339 | 3.68 | 393 | 5.99 | 81.64 | *** |

| Reading a mag | 230 | 2.50 | 358 | v.45 | 59.64 | *** |

| Playing board games with my peers | 135 | 1.47 | 187 | 2.85 | 27.46 | *** |

| Watching YouTubers on my mobile telephone | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | |

| Not stated | 9204 | 6563 | ||||

| Publisher'southward Notation: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 past the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This commodity is an open access commodity distributed under the terms and weather of the Artistic Commons Attribution (CC By) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/16/8352/htm

0 Response to "Positive Effect of Cell Phones on Families Google Scholar"

Post a Comment